THE SUNDAY TRAVEL SECTION of the New York Times would seem, on the face of it, an unexpected venue for an artistic confession, but for the multifaceted Jennifer Anne Moses—fiction writer, spiritual memoirist, and painter, as well as a self-confessed “liberal East Coast Jew”—it was an acutely appropriate venue, effectively the still point of her turning world.

In her twenty-odd-year career, Moses has written, then painted, from the thematic heart of this nation’s Official Culture, the Washington-to-New York-to-Boston corridor—though, movingly, from its edges: however much she has been a privileged insider (which she openly avers), she hasn’t much felt like one, and that vulnerability has given her an ability to see across our many cultural divides with humor and compassion.

No wonder, then, that the Times would be the perfect place to recount her Louisiana to the rural home of her closest muse, the mid-twentieth-century African-American painter Clementine Hunter.

First, though, a word is in order about the pivotal role of Louisiana in Moses’s artistic development, both literary and visual: after a season of at-home mothering and writing from her home in Washington, DC, in which she published short stories and Washington Post features that earned her the title of “the Erma Bombeck of the Beltway,” in 1995 her husband took a job as a law professor at Louisiana State University, and the family moved to Baton Rouge. Moses’s encounter with the state, in its multiple dimensions, altered the course of both her art and her Jewish practice. After Hurricane Katrina, her essays and op-ed pieces—and later, her paintings—brought her to some fleeting national prominence as one of the “voices” of the disaster.

But more about that later. In 2008 Moses and her family returned north, this time to New Jersey. The impetus for Moses’s 2013 pilgrimage to Louisiana, which she documented in the Times, was seeing a performance of Robert Wilson’s opera Zinnias: The Life of Clementine Hunter. Born in the late nineteenth century when “slavery was an institution of living memory,” as Moses relates at the start of her piece, Hunter was “in her fifties [when she]…picked up a paintbrush and embarked on what became a remarkable career.”

The bulk of Moses’s essay is focused less on the logistics of the trip than a frank, lush appreciation of the in situ examples she finds of Hunter’s work, which became an early standard-bearer for the “outsider art” movement: Hunter painted mostly imagined scenes from her rural life, by her own lights, adorning an array of discarded household objects as well as canvas. Many of these are of black Christian religious scenes: Moses cites among her favorites a full-immersion baptism, and a rural wedding in which “the bride is by far the largest figure,” which she theorizes may be “an example of how the artist made those figures who were important to her…larger than those whom she deemed insignificant or otherwise uninteresting.” She points out how many of the paintings are funny, such as a juke joint painting labeled simply “drink, dance, get shot.”

On the subject of the work’s formal properties, Moses exudes the most passion:

[Y]ou can see how thickly the artist applied her paint, sometimes in globs, creating, for example, textured and shadowed loads of cotton. But pretty much all the paintings in this room dazzle by their palette alone: deep reds and yellows; astonishing turquoise-lavender blues; lollipop orange; ebony black…. Though childlike in the rendering, the work transcends itself, becoming not only a record of a way of life…but also of what must have been Hunter’s own joie de vivre, her own love of color and the natural world, and most of all, what must have been a killer sense of humor.

Moses wraps up the profile with this heartfelt admission of her own relation to her subject:

[W]hen I moved to Baton Rouge in 1995, after having spent my life on the East Coast, my own head swelled, or perhaps spun would be a better word, as I had yet to learn how to take in my new, deeply religious Southern world. But by gazing long enough at the joyous and astonishing art of Clementine Hunter, I eventually grew a better set of eyes.

Hunter’s work touched something in Moses that was rooted deep in her soul, but which her own childhood and background had not allowed her to explore. Growing up in “a starkly white modern house surrounded by woods and streams in McLean, Virginia, the second of four children of assimilated, athletic, well-educated, and wealthy German Jews,” Moses had both spiritual and artistic leanings, but left these behind amid what she describes as the “insane game of competition” in her family, which continues, at least a little, to haunt her: “My academic abilities were just fine,” she told me in a June 2012 interview, “but since I didn’t go to an Ivy League college, that was always ‘second best’ in the family view.”

Instead, Moses became a writer. As a young DC-based wife and mother with a husband who was an associate in a powerful downtown firm, Moses published short stories in literary quarterlies and—in the era right before the advent of “Mommy blogs”—humorous Washington Post features about parenting in her “all Volvo” neighborhood.

Yet even in the midst of this successful and privileged life, Moses remained conscious that something was missing. Food and Whine, her humorous 1998 memoir about cooking, writing, and mothering as her own mother was suffering from cancer, describes the pallid, careerist Washington, DC, milieu in which, as the wife of an attorney in a white-shoe firm, she was immersed. Of a formal downtown event she and her husband attended, one that ultimately spurred a fight between them, she wrote:

And sometime during this party I started yawning and making remarks about how much I missed being around the kind of interesting people I used to hang out with before I got married—people who were able to sustain a conversation about something other than the use of corporate torts in the deregulation of the cable television industry.

Moses’s turn to painting came after several transformational experiences that she documented in her 2007 memoir, Bagels and Grits: A Jew on the Bayou. After making her home in Baton Rouge, once all of her children were old enough to attend school, Moses began volunteering at a Catholic residential home for AIDS patients. She wanted to get out of the house, to give back to the community, but also “because Jewish tradition…instructs us to visit the sick. The Talmud goes as far as to say that he who doesn’t perform this commandment is like one who sheds blood.”

At Saint Anthony’s, the residents were largely African American and indigent and—whatever wanderings, drug abuses, crimes, or other forms of faithlessness had marked their lives, Moses noticed—were almost always quick to call upon the language of the Bible and the name of Jesus as a source of hope.

Initially, Moses found this unexpected piety unsettling: “As a child growing up in McLean, Virginia…I didn’t know anyone, either Christian or Jewish, who professed any kind of real faith…. No one in our circle, even among the church- and synagogue-goers, was truly a person of faith, by which I mean a person who counts God among his inner circle.”

But quickly she found that she preferred that kind of ecstatic spiritual intimacy to the conceptions of Judaism around which she had been raised, which focused more heavily on ritual, communal identity, and defense of Israel than on any particular notion of God. “I, too, wanted to be filled with a faith so buoyant that it could carry me beyond myself, beyond sorrow, beyond memory even, and right smack into the embrace of eternity.”

Moses frames her turn to painting as the result of her own mystical experience: at Saint Anthony’s, she told me, the health aides would all sing hymns and gospel songs. “And I wouldn’t join in because I can’t sing,” she says. “The health aides were insistent, ‘If you pray to Jesus, he’ll give you a voice.’ Now, I am absolutely sure that Jesus is not my way to the Divine but Jesus was Jewish. I was sure it would come, but it didn’t.” Moses’s eight-year-old daughter Rose, meanwhile, had been bugging her mother to buy her art supplies.

One day two or three weeks after Moses began praying for a singing voice, she set out the paintbrushes and paints. Her daughter began working on a painting, and Moses joined her and started one of her own, a portrait of Saint Anthony’s residents that drew from her encounter with the spiritual and artistic currents—including Clementine Hunter—that surrounded her: she cut out photographs of residents and pasted them to the canvas, then made them into flying angels with haloes and wings. Her daughter quickly abandoned her attempt, but Moses’s painting career was off and running.

“That’s how I understand it: God granted my prayer,” she says. “God didn’t change my physiology, but something that was already there was ignited.” While her Saint Anthony’s colleagues viewed the painting as a testament that Moses has “got the Holy Ghost,” Moses’s rabbi at Beth Shalom Synagogue credits the inspiration to the “Shechinah, the Joy of Israel.” Out of a crisis of faith, she emerged enlivened and ready for a more dynamic (and for that matter, charismatic) form of Jewish practice.

All of these influences come dynamically together in the many paintings Moses has produced and exhibited in the decade since, particularly those collected in the Pages of the Torah exhibit, which I saw at the Historic Sixth and I Synagogue in Washington, DC, in September 2012. At the opening, Moses read from her latest work of fiction, Visiting Hours, a collection of short stories drawn from her volunteer experience at Saint Anthony’s.

Pages of the Torah is a series of paintings based on the narratives of the Hebrew scriptures—though maybe in this case, given that the critical thematic element of the paintings is Judaism’s intersection with black Christianity, the term “Old Testament”—ordinarily considered disparaging to Jews—is warranted.

Moses has developed a painting style that, in general, follows many of the visual conventions of what has been commonly termed “outsider art”: childlike figures, mystical, and also mythical, visual compositions that stretch boundaries of time and space. In other words, visionary art—to employ the term used by the Baltimore-based museum that is entirely devoted to this wide-ranging genre. The look and feel of Moses’s paintings echo Clementine Hunter, as well as other well-known figures like Howard Finster and Myrtice West. Furthermore, as Monica Kjellman-Chapin notes in the essay “Fake Identity, Real Work: Authenticity, Autofiction, and Outsider Art,” outsider artists are also typically characterized as “distant from or irrelevant to the institutions of [the mainstream] culture.”

But the breadth of visual references in Moses’s work—symbols, in-jokes, and quotations—stretches far beyond the standard body of tropes used in most works (and by most artists) of this kind. I have quoted at length from Moses’s writings above to give a sense of the thematic range of the subjects referenced in her paintings, and also to convey the similar spirit that animates both her visual and written work.

Which is not necessarily to claim a greater depth or relevance for this work than for that of her antecedents.

A nagging question remains, though: is this just another example of, say, former London School of Economics student Mick Jagger appropriating the Mississippi Delta and Robert Johnson in covering “Love in Vain”?

The answer to the question, and the value of Moses’s approach, I would aver, lies in the authenticity and vibrancy of Moses’s own passion for her sources, and her daring willingness to marry outsider visual conditions with the Jewish mystical tradition.

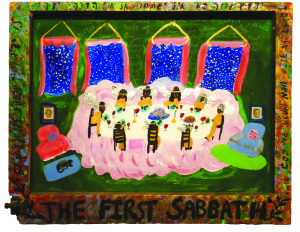

PLATE 7. Jennifer Anne Moses. The First Sabbath, 2011. Mixed media on paper in cast-off wooden window frame. 22 x 29 inches.

The First Sabbath, the first painting in the cycle, is characteristic of Moses’s approach: painted on a window frame, the work embodies similar formal conventions to that of Hunter and other outsider artists: the bright, saturated colors, the puffy-pink brush-stroke clouds signifying that these events are taking place in the spiritual realm [see Plate 7]. But whereas a Christian evocation of the first Sabbath would likely focus on the inauguration of the day of rest through the ur-image of, say, a white clapboard country church filled with winged angels, the center of this composition is the Shabbat dinner table. Look even closer: the words of Hebrew prayers are calligraphed around the window frame’s edges.

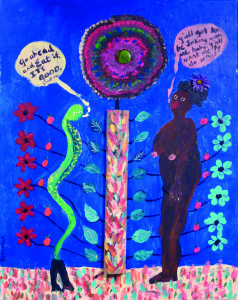

The Tree, Moses’s depiction of Eve’s temptation by the snake, preserves the brilliant colors and simple figures used by Hunter, but the whole composition, the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil in this Garden of Eden, and the vegetation surrounding it, is stylized and proportionally balanced in a manner more exact than what you usually see from Hunter or most outsider artists [see Plate 11]. Right at the center, the tree pops up like a stark modernist lollipop.

There are other resonances that would seem to be beyond the ken or intention of outsider-art conventions, especially ones drawing from black Christianity: the shape of Moses’s brown-skinned Eve, evoked in thickly layered and multihued paint, with rounded hips and great pendulous breasts, closely echoes the Venus of Willendorf. And while a curvaceous and unclothed Eve hews fairly closely to what you might see in the paintings of many outsider artists, this Eve’s cake-icing-pink nipples and visible pubic hair depart from the prim sexual reticence that seems characteristic of much outsider painting on biblical themes—in contrast to the exuberance of their spiritual themes.

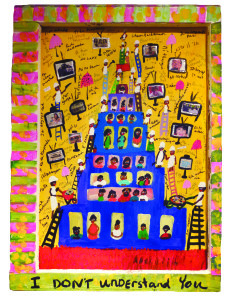

PLATE 9. Jennifer Anne Moses. I Don’t Understand You (Babel I), 2010. Mixed media on paper in cast-off wooden window frame. 30 x 22 inches.

Within the Pages of the Torah cycle, three paintings exploring the story of the Tower of Babel offer insights into the assortment of Moses’s influences, as well as her own emphases in what are ultimately deeply evangelical works. In the first painting of the series, I Don’t Understand You (Babel I), dozens of African-American figures are building the legendary tower in the form of a stepped, cobalt-blue pyramid against a rich golden-yellow background, with wheelbarrows and stacks of bricks beside them [see Plate 9]. Meanwhile, within the blue pyramid, rows of windows on each level each frame a single African-American figure.

The meticulous ordering and stacking of figures is common to much outsider art—the paintings of Howard Finster, in particular, with their arrayed clusters of bright-eyed faces, though the faces in his paintings are more typically white. (Think of his cover for the 1985 Talking Heads album Little Creatures.)

The visionary scene is also sprinkled with written phrases in many languages, representing the Tower of Babel’s mythical role in the origins of language in general, and human discord and misunderstanding in particular.

Finally, flying in the air around the frame of the tower are a number of television sets—the medium most contributing to the proliferation of “babble,” presumably—into whose screens Moses has inserted small, cut-out photographs, in the tradition of Clementine Hunter.

As much as the painting follows conventional tropes, the work represents a considerable elaboration on them: the easy familiarity with languages, even if only superficial, betrays that this artist cannot be characterized as “distant from or irrelevant to the institutions of culture.”

That same mix of outsider technique and worldly values carries through the other two Babel paintings, and is extended even further. You Talkin’ to Me? (Babel II) features the same pyramidal tower, painted in red and even more monumental this time, with clustered rows of windows and without human figures. (It reminded me, in fact, of another Babel: the long-unfinished skyscraper Ryugyong Hotel in Pyongyang, North Korea.) Flying around the sky-blue background in Babel II are a series of zany multicolored helicopters, sprinkled with profanities and epithets that would seem to embody the artist’s sense of humor—well evident in her writing, and a trait she admired in Clementine Hunter. But the piece’s largest cultural “nudge” turns on the title, the refrain of Robert DeNiro’s character in the 1976 film Taxi Driver, the delusional Travis Bickle, who wants to use violence to be massively, publicly “heard” after a lifetime of feeling isolated.

PLATE 10. Jennifer Anne Moses. Babel Inc. (Babel III), 2011. Mixed media and collage on board. 23 x 31 inches.

Of the three paintings in the Babel cycle, Babel, Inc. (Babel III) draws in the most references from outside the biblical narrative, and consequently raises questions about Moses’s overall oeuvre and its relation to outsider art conventions [see Plate 10]. This time, the pyramid is devil red, and flanked by massive Satan figures holding pitchforks. Lined up along each of the pyramid’s levels are small cut-out pictures of presumably “evil” public figures, from Hitler and Mao Tse Tung on the upper levels to George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, and Sarah Palin below. (I happened to be attending the exhibit with a Republican family member, whose response was a distinctly grumpy “Hmmh.”)

That explicit political appeal is well within the canon of mainstream media expression, of course, but how does it relate to the artistic conventions of outsider art that Moses has embraced, since clearly, this is not the work of an outsider?

In addition to the outsider artist’s “social marginality” and position outside “the institutions of culture,” Kjellman-Chapin also discusses the critical role of an artist’s biography in establishing—or perhaps justifying—that outside role. (The bulk of her essay, in fact, discusses several cases in which the “biographies” of outsider artists, including the fictional Toronto artist Joseph Wagenbach, a longtime recluse who died leaving a household of handcrafted art objects, were in fact elaborate hoaxes executed by artists well connected to the official networks of galleries and critics.)

Clearly, issues of biography always press in from the edges of Jennifer Moses’s work, however much she makes use of biblical themes or aspects of African-American culture. We Love You Emerson, a painting outside the Pages of the Torah exhibit, is illustrative of this tendency. The painting is of a black funeral service, with the composition of the sanctuary rendered in bright bands of color. There is a field of gold on which are arrayed congregants in pews, and a hot-pink altar, really more like a stage, where a minister and a mourner balance the open coffin of the deceased Emerson. Finally, behind the altar are broad church (or funeral chapel) windows, not of stained glass, but rather a deep midnight blue, studded with luminous silver pinprick stars. (Full disclosure: I own this painting.)

A full appreciation of the work is found outside the frame: the painting’s resonance flowers even further when one learns that Emerson is the noted Baton Rouge painter and sculptor Emerson Bell, who died in 2006. Thus, instead of illustrating any kind of private spiritual revelation as a result of this funeral, the painting actually establishes the artist as a consummate insider in the art scene of her adopted hometown.

Or maybe not: the details of Moses’s biography can, rather, serve to underscore the raw spiritual force of mourning that is evident in this open-casket funeral setting, and which was likely unfamiliar to Moses. In a vignette in Bagels and Grits, Moses describes attending the funeral of the husband of a fellow parent at her children’s school, at an African-American megachurch, and seeing this widow perform a liturgical dance as part of the ceremony. Attired in a sparkling red outfit, this dancer became the concrete expression of the kind of enlivened, say it, charismatic religion—and authentic connection to God—that Moses was seeking.

Moses’s paintings become, then, the outworking of her spiritual aspirations, the concrete embodiment of the kind of prayer, and faith, that she has witnessed in her Baton Rouge confreres, but knew nothing of in her former East Coast life. Moses thus, in fact, truly is an outsider, if we look at being an outsider through this inverse lens, as a spiritual condition.

To some extent, you can set Moses’s spiritual affiliations within the language and practice of Jewish Renewal, a movement that crosses the denominational lines of mostly Reform and Conservative congregations, and which, during the last forty years or so, has effected a kind of mini Great Awakening or Azusa Street moment in the faith: worship is more emotive and focused on spiritual inspiration, and draws upon Jewish mystical, particularly Hasidic, traditions.

The Jewish Renewal movement is notable for its willingness to integrate spiritual insights and rituals from other mystical faiths, particularly Sufism and Buddhism. Given the troubled history with—and persecution by—Judaism’s daughter religion, though, these appropriations have typically not been from Christianity, although there have long been resonances between Judaism and Quaker and Unitarian traditions.

The dizzying references and visual juxtapositions of Moses’s work can also be situated within the larger emergence, during the last forty or so years, of the discipline of southern studies. Steered in large part by former NEA chair Bill Ferriss out of his original work in what was then called “Afro-American studies,” the new discipline has raised awareness of the multivalent cultural space of southern identity, and how various strands of culture influence or speak to one another. Its foundational tome, The Encyclopedia of Southern Studies, illustrates the sometimes rather jarring juxtapositions in this cultural soup, with profiled subjects ranging from the KKK to the temperance movement to the meaning of bottle trees to the reasons for historic tamale stands in the Mississippi Delta.

One of Moses’s most vital contributions to that body of southern studies is likely to be her work that grew out of her family’s experience in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. From fall 2005 until well into 2006, Moses penned a number of op-eds for the Washington Post, her former hometown paper, that provided a window into the ongoing hardships that the state faced, with titles such as “Still Drowning in New Orleans,” “Katrina’s Unsung Victims,” “Katrina’s Trailer Exiles.” And, perhaps most interestingly, given her biography—there’s that biography again!—“Why Baton Rouge Is Still Bush Country.”

PLATE 8. Jennifer Anne Moses. Like New Orleans, Only Bigger, 2010. Mixed media, spray paint, and collage on paper in cast-off wooden window frame. 22 x 28 inches.

Hurricane Katrina also exerts a powerful influence in Moses’s paintings: in the Pages of the Torah cycle, Like New Orleans, Only Bigger brings Katrina together with the narrative of Noah and the flood most movingly [see Plate 8]. Upon a background washed with layers of aqua and periwinkle, Noah’s ark both floats and presides, with a waving Noah, wife, animals, and dove. But there is also a row of houses whose flooding is obliquely evoked by the streams of water, like tears, that flow from their window frames. In addition, a line of floating bassinettes holding black babies constitute little arks, and perhaps also a reference to Moses. Outside the canvas, the Noah theme is carried out in the line of animal-shaped cut-outs studded around the gold-painted frame.

But it is the text scrawled across the top of the composition that carries all those images from the mythic to the religious: Amazing grace / Look like we finally gon get us some relief / Praise the Lord / He might not come when you want Him but He always come on time / it sure has been a big old storm / Thank you Jesus.

Toward the end of Bagels and Grits, Moses gives an account of a harrowing car accident that she and her husband suffered in Tucson, Arizona, a city to which they are contemplating moving. It was an accident in which they could have easily died. The shock, and the implications, serve as a ratification for Moses that she must continue to turn from the preoccupations of the world and focus on the things that are essential:

In his Mishneh Torah, the medieval Jewish philosopher Maimonides writes that the cry of the shofar on the Holy Days of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur is “an allusion, as if to say, Awake, O you sleepers, awake from your sleep! O you slumberers, awake from your slumber! Search your deeds and turn in teshuva [repentance].”

All of Moses’s paintings are an amplification of this call.