Neither the action nor the actors can be anticipated…. They begin as an unknown adventure in an unknown space.

—Mark Rothko, 1947

OUR ENCOUNTER with reality is endlessly generative. Both Subject and Object, the contemplative and the contemplated, are replete with a beautiful, orderly complexity. The authentic artwork—glittering, effulgent with metaphysical glory—bears witness to the felicitous collision of Subject (knower) and Object (known). The result is like tall waves crashing on a beach, like the spiraling smoke from a fire, like the light of colliding stars. The Subject (the artist) possesses a complex inner life that equals the complex outer life she humbly contemplates. Form, bell-like, chimes upon answering form; echoes spread through the air, concentrically, shifting from the brassy, sacred violence of the first moment to mellow tones of cast-off sonic radiance. Throughout the course of art history artists have favored one “side” in this artistic collision over the other. Some artist-Subjects have subordinated themselves to their contemplated Object, striving to picture the Object in its fullness, working to suppress the spiritual and emotional baggage they bring to an endeavor meant to be pure. Other artists turn in wonderment to the action of their own souls, the structures within: the architecture of that inner self that permits the collision (or should we say the marriage) of the Subject with the real, external thing.

The visual and performance artist Lia Chavez is interested in the Subject’s potential to create. In her recent work, Chavez has aimed to map the creative process by delving deep inside and recording what she finds there. Accordingly, her Object is most properly herself, but at the same time, her Object is everything. For Chavez, inner and outer space are connected, both literally and through the production of certain congruencies that exist between the mind, the world, and the cosmos. Chavez herself cites as inspiration a sheet of drawings by Leonardo da Vinci in which the great master juxtaposes an image of a pensive philosopher with a sketch of rushing water. For Chavez, da Vinci’s drawings show that consciousness flows the way water flows; the whorls and waves of water echo the whorls of consciousness, not coincidentally, but through the grace of divine design. We are the universe and the universe is us. We are shot through with order and cosmic light. God’s beautiful ornaments—informed by the exquisite fractal nature of the universe—are everywhere. Consider Chavez’s haunting photograph Last Confessions of a Dying Star [see Plate 20]. This image simultaneously evokes cosmic phenomena, the travails of human embodiment, the locomotion of cellular organisms (with arms like flagellae) and, if Chavez’s intuitions are right, the flow of consciousness intrinsic to the creative act.

Looked at a certain way, the modernist project can be understood as a quest for the font of inspiration. Reacting against the relatively detached medium of photography, some of the earliest modernists—Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Paul Cezanne— strove to record their subjective “impressions” on canvas. Later artists delved further inward, until, like Vassily Kandinsky or Piet Mondrian, they learned to map their brushstrokes to purely spiritual intuitions that reflected not the outer world, but an interior one, or at least a more elevated one, in vibrant colors and sinuous or stentorian lines. By the time Jackson Pollock emerged with his distinctive drip paintings in the 1940s (influenced, surely, by the Zen lionization of the autographic stroke), art had become a matter not of picturing but of channeling: Pollock declared “I am nature,” and his works issued immediately from his experience of the forces of the universe, not from any need to optically record.

But this trend toward achingly frank metaphysical disclosure was short-lived. Pop Art brashly mocked the sincerity of its art-historical predecessors. Minimalism championed the literal, the blank, the banal, in favor of a different kind of experience—not one of plunging soul-communication, but one of contact with an obdurate object that pushes back. Conceptualism favored rational intellect over intuition. All of these movements, when compared with the abstract expressionism of an earlier era, were hard-boiled and cynical. All of them implicitly rejected the notion that art was about an ecstatic, subjective experience of inspiration. All of them strove to return art to a more arid, more forthrightly propositional plane.

Lia Chavez is aware of her place in this decades-long history. And she advances art history by looking backward—back toward the throbbing sincerity of the abstract expressionists decades before, and, thanks to her admiration of medieval and Renaissance artists, further back still. Her work is all about tracing inspiration to its roots and discovering, like Jackson Pollock, that we “are nature,” that all of us “are nature,” and that inspiration comes from the simultaneously earthly and divine sources at the heart of Being.

PLATE 21. Lia Chavez. Luminous Objects, 2013. Performance work at the home of Chiswell Langhorne, Sag Harbor, New York. Presented at the Armory Show Summer Celebration in the Hamptons.

Lia Chavez herself is slender and delicate. Her dark hair contrasts dramatically with her pale skin. She can be radiant with confidence, loquacious, articulate. She is passionate about her artistic program. She is warm and encouraging and prodigal in the distribution of her affections. She is breathlessly, unstintingly positive; there is not a cynical bone in her birdlike frame. At the right moment, she can be elegant. In fact, she can pull off “glamorous,” and that is well, because her circumstances often demand it. For paradoxically, given her sometimes childlike mien, Chavez must inhabit the role of the New York socialite. A noted hostess of artists’ salons, Chavez indeed lives a life that approaches a kind of theater. In a recent performance titled Luminous Objects Chavez, wearing a billowing white gown, meditated among trees on a lush Hamptons lawn [see Plate 21]. Her personal effervescence and graceful appearance are integral parts of her artistic project.

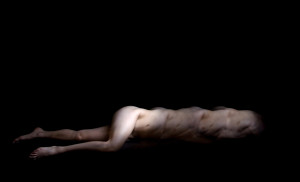

The daughter of a scientist and an artist, Chavez grew up with a Christmas tree all year round, its trimmings changed to fit the season. She was the well-loved eldest among four children in a small town in rural Iowa. In high school, Chavez allied herself with interestingly unsavory elements, though she herself was a model student and, in the eyes of her elders, precociously wise. As an undergraduate at the University of Denver she combined her love of art with a passion for international affairs; she wished to become an artist-ambassador to the world. Later she traveled to England to complete a fellowship at the International Gender Studies Centre at Oxford University, and indeed some of her photographs seem to have a feminist subtext—an ambiguous sense of sexual violence—like Helix Nude [see Plate 22], wherein an impossibly twisted female torso gropes heavily, incrementally, impossibly, along an ink-black ground.

Chavez’s recent oeuvre is startlingly diverse, ranging from photography, painting, and drawing to performance, sculpture, and installation. Common to much of her work, however, is the conviction of a kind of congruency among facets of the physical world: the mind, the ocean, weather patterns, celestial bodies, the spirals in the center of flowers. All of these are shot through with the same forces—all of them share the same structures in their inner life. Chavez is preoccupied with light, both in its appearance and its ephemeral substance. Her three most recent bodies of work, A Thousand Rainbows, True Light, and Luminous Objects each reference light in their titles, and each works with the concept of light in its physical manifestations. Indeed, Chavez seems like a modern-day Franciscan in her conviction about the analogic ability of light to evoke the divine. In the same way that Saint Francis of Assisi, in his Canticle of the Sun, saw divine meaning in “Brother Sun, who brings the day,” so Chavez views light as a type both of the divine substance and the lofting, penetrating faculty of the mind.

In A Thousand Rainbows, a series of works executed in 2011, Chavez strives to echo a cosmic process: the passage of light from object to object—specifically from distant star to the human eye. The heavens we nightly behold are filled with star-points of light that originated at different points in space-time; these lights have traveled vastly divergent distances to the beholder. Some of the stars we behold may have died before their light reaches our eyes, but we see them alongside other lights nevertheless. In A Thousand Rainbows, Chavez creates stop-motion images of human bodies whose reflected light likewise originates at different points in time, but whose images appear simultaneously. Consider Andromeda [see Plate 23], named for the galaxy, where points in the swirling trajectory of a graceful, curved arm, originating from the same dancer moving through space, are recorded in a coincident way. For Chavez, the photography is a two-way process: the object of contemplation impacts the artist, yes, but the artist impacts her object, as well. Thus Chavez is a full, bodily participant in the creation of her Thousand Rainbows series. Clad in black, she directs and interacts with the dancer she photographs. She is present invisibly in every photograph she creates.

In her bravura performance True Light, Chavez claims direct inspiration from a medieval figure who clearly anticipated Franciscan spirituality. In the accompanying artist’s statement, Chavez quotes the twelfth-century Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis, the first Gothic impresario, as he contemplates the stained glass and gold of his masterwork, the French royal church of Saint-Denis: “Bright is the noble work,” Suger says of his creation:

but, being nobly bright, the work should brighten the minds, so that they may travel, through the true lights, to the True Light…. The dull mind rises to truth through that which is material and, in seeing this light, is resurrected from its former submersion.

For Suger, art and the light that illumines it rescue the mind from both sin and banality. At Saint-Denis, a splendid fabric of glass and gold gives form to light, and it is through these forms that the mind approaches the resplendent form of God. Suger’s words (and Chavez’s theories) also recall the thoughts of neo-Platonists like Plotinus and his later, Christian follower, the mysterious Dionysius the Areopagite. For Suger and Chavez, the whole world is illuminated with divine similarities.

PLATE 24. Lia Chavez. True Light: Heal Us/Heal U.S., 2012. Zuccotti Park, New York. Water, Mrs. Meyer’s All Purpose Cleaner, sponge mop. Still from the documentary The Journey: Lia Chavez True Light.

Chavez’s True Light, performed between September 1 and December 1, 2012, was a feat of endurance. The artist fasted for ninety days broken into a trinity of thirty-day units, each with a different focus: thirty days of prayer were followed by thirty days of meditation, which in turn were followed by thirty days of total silence. This process, during which Chavez utilized her self-imposed deprivation to access her inner source of creativity, resulted in additional performances and objects inspired by the devotional experiences comprising the main body of the work. During her ninety-day fast, for example, Chavez was moved to go out into the streets of New York City and engage passersby in a performance inspired by the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. This performance, staged on the eleventh anniversary of 9/11 and titled Heal Us/Heal U.S., involved a mop and a dirty, busy street: the artist, over the course of several hours, traced and retraced the words “heal us” on a city sidewalk [see Plate 24]. The words themselves evaporated each time Chavez inscribed them, but slowly the pavement paled from the cleaning.

PLATE 25. Lia Chavez. True Light: Form of the Infinite, 2013. Performance work, presented at TEMP Gallery, New York.

Other products of Chavez’s True Light performance have been presented in a more traditional gallery setting. True Light: Form of the Infinite, for example, was birthed from a central insight Chavez gleaned from her month of silence. Stunned, after thirty mute days, by her experience of the sudden resonance of voice through matter, Chavez strove to create an installation that would unveil the mysterious physicality of human speech. Thus she created an object she dubbed the “double bell,” whose highly sensitive latex surface reacts to the vibrations created by a properly channeled voice. In her performance, Chavez coated the latex surface with sand, conducted her voice into the “bell,” and projected the sand’s changing configurations onto a screen [see Plate 25]. Improvised song, as immediate creation, was transformed into something visually dynamic, in a drawing of similarities between intuition, image and sound.

The act of tracing the creative process is central to all of Chavez’s works, but certain pieces more overtly privilege process over aesthetics. True Light: Dynamic Images, for example, consists of a series of photographs that do not register any external object, but that instead capture, in the circumstances of their making, the span of a prolonged prayer. During the course of Chavez’s True Light fast, sheets of photosensitive paper were nightly exposed in a dark room while the artist prayed. The result is a sequence of images of almost perfect whiteness, though small differences reflect the duration of each prayer. True Light: Dynamic Images explores how spiritual and physical pressure cohere to leave a simultaneously earthly and divine trace. The physical appearance of the work is only a small part of its message. To appreciate the work, viewers must be mindful of how it was made.

PLATE 26. Lia Chavez. True Light: Material Dispersion, 2012. Purified spring water, glass bottles, aluminous caps. For Wallis Annenberg, Jeffrey Deitch, Eli Broad, John Baldessari, Ed Ruscha, Chris Burden, Karin Higa and Michael Ned Holte, Ann Philbin, Michael Govan, and Paul Schimmel.

A third product of Chavez’s ninety-day True Light fast, True Light: Material Dispersion, likewise depends on a spiritual backstory for its full impact. In Material Dispersion, Chavez filled several identical jars with water; the water trapped in the clear vessels is meant to alert viewers to the way physical substances, and by analogy human consciousness, can refract real or spiritual light [see Plate 26]. In the form reproduced here (and Chavez has explored a variety of configurations), Material Dispersion is not visually unique: the sequential arrangement of jars recalls the regimented glass structures of Josiah McElheny’s famous Modernity Circa 1962, Mirrored and Reflected Infinitely [see Image Issue 61]. However, while McElheny’s arrangement of glass objects is meant to comment on the utopian ideologies of the middle twentieth century, Chavez’s piece has more frankly spiritual goals. As in True Light: Dynamic Images, prayer is central to Material Dispersion. Each jar has been blessed and has in turn been dedicated to a different art-world figure. And unlike in McElheny’s piece, each jar is destined for a different resting place; in the same way the refracting action of the contained water distributes light, so Chavez plans to distribute her sacred jars to the recipients of the prayers she has offered.

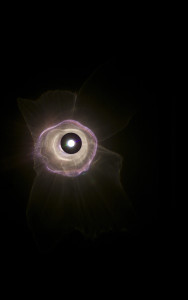

PLATE 27. Lia Chavez. Luminous Objects: An Exploding Star Is an Inverted Eye, 2013. Optical device sculpture, installation view. Blown glass, distressed plastic, anodized aluminum, krypton incandescent bulb.

In many of her artistic projects since 2011, Lia Chavez has aimed to demonstrate the resonances among physical and spiritual phenomena. She has aimed to show how inner space mirrors outer space, and how both mirror the invisible laws of the universe. Her current performance-project, Luminous Objects, attempts, beyond all of her earlier efforts, to fulfill the promise of her theory of creativity. If the vicissitudes of creative consciousness truly echo the ebb and flow of the material world, if these two things are truly congruent, then it stands to reason that some visual evidence—some trace of these harmonies—could be produced “from the source,” as it were.

In Luminous Objects, Chavez aims to lay bare the form of inspiration by diving for prolonged periods into the depths of consciousness—the very depths from which creativity arises. After years of study, Chavez has concluded that artistic creativity is associated with theta brain waves; she further believes that she has honed a technique of descending into a theta state at will. Thus situated at the font of creativity, Chavez opens herself to internal visions, which she records as drawings and writings (and in at least one case, as a sculpture: An Exploding Star Is an Inverted Eye [see Plate 27]). The first visions Chavez received through this process were Freudian—phallic, erotic—but after prolonged meditation her inner images transformed into cosmic revelations reflecting the selfsame universal resonances that Chavez has long pursued. These drawings have yet to be released, but they will be reproduced in book form in 2014. Upon their release, audiences will have the best chance yet, perhaps, to test Chavez’s process against her products—to see if inner- and outer-space truly mirror each other after all.