WHEN I WAS A CHILD, I found, embedded in one of my parents’ liqueur bottles, a tiny brass wine goblet, a decorative marketing ploy. The toy-like quality of the goblet and the forbidden place I found it made it irresistible to me. I’ve kept it through the years: too small to display but too precious to throw out, this miniature object has captivated me.

The miniature, as a form, offers endless fascination—perhaps because it targets our vanity, perhaps because it allows us the joy of reveling in creation, of seeing the world from a new perspective. To capture an exact likeness of something life-sized, monumental, or even catastrophically gigantic—either in its literal or ideological size—allows us to own it in some respect. Some of humanity’s earliest art, like the tiny carved statuettes of stylized, fleshy female shapes from the Paleolithic era, shows just how long this drive has been with us. These ancient figurines (most notably the Venus of Willendorf, at just under five inches tall) are among the earliest expressions of the human form, and are thought to be fetish objects to be held in the hand as talismans. They exemplify the idea that representations of life contained a kind of protective magic. The miniature tames the things we fear, the uncertainties we seek to guard ourselves against. Being able to hold onto a tiny assurance of protection allows us to cross into territories where we wouldn’t otherwise tread. Doppelgangers of real life, miniatures can act out threatening or hopeful scenes without true danger or consequence. Yet they can unsettle as well as comfort us. Their very unreality is a poignant reminder of the fragility of our lives. The tiny goblet and the Venus figures may represent our desires and hopes—for sophistication, for children—but they cannot in themselves bring about these goals. They may even become reminders of our failures. They echo their giant siblings but can’t fulfill their function. A miniature is a dubious twin.

Barry Krammes’s most recent work rests on the dual nature of the miniature as both intimate contemplative object and Freud’s concept of the uncanny double. In his essay “The Uncanny,” Freud describes our desire to preserve ourselves through different kinds of doubles—mirrors, shadows, representative objects, and concepts like spirit or soul. The double, he says, originated in our desire to safeguard the ego against extinction, but since it also reminds us of the thing it is supposed to guard against, it also becomes “the uncanny harbinger of death.” A series of tableaux concocted from found objects and purchased antiques, Krammes’s new works function like postmodern altarpieces, drawing the viewer into meditation while also conjuring an underlying doubt.

In his essay Simulcra and Simulations, Jean Baudrillard wrote that “reproduction is diabolical in its very essence; it makes something fundamental vacillate.” A miniature reproduction is even stranger still, doubly removed from its origin (by size as well as by its imitative nature). A found object reused as a miniature is something between an imitation and the real thing. Distanced from its intended function, it serves as a reminder of what is absent. It simultaneously stands for and negates the object it represents. In this sense, the miniature has an estranged relationship with the viewer. It provides a temporary space of intimate contemplation—a safe space to act out the things we fear—while at the same time causing us to doubt their validity. The reproduced miniature is not a copy of an object but its double; it is what Baudrillard calls a “simulation.” This kind of miniature goes beyond the cute collectible; it threatens “the difference between true and false, between real and imaginary.” Its very ambiguity imbues it with magic. Like the Venus figurines, the miniature shares characteristics of what it represents but is an inexact copy.

Previous to his recent series of works, Krammes invested over two decades in the medium of assemblage art. Assemblage is the three-dimensional equivalent of the collage techniques invented by Picasso and Matisse. The process transforms found objects into sculpture via gluing, soldering, or welding. The idea is to piece the objects together without deliberation so that the finished piece suggests subconscious meaning. Krammes’s foundation in assemblage provides the underpinning of this new series of works. While they inherit elements from assemblage, their deliberateness, theatricality, and use of narrative makes them something very new.

Of Calamities (2007) exemplifies Krammes’s use of the uncanny double [see front cover]. It portrays a miniature carousel that has been bashed and crumpled by an unseen force of nature. Inspired by a 1938 photograph of a real-life carousel that suffered hurricane damage in Providence, Rhode Island, the miniature version is a tiny theater of devastation. The twisted metal and tiny writhing figures are at once disturbing and entertaining (it’s made of beautiful antique toy carousel pieces, a menagerie of tiny animals and friezes) [see Plate 4]. My attraction to the piece feels similar to my fascination with CGI visions of total global destruction in movies: it leads me into the territory of deep, semiconscious fear, but taking pleasure in fictive damage feels harmless enough. As we look at an imitation of the wreckage in Providence, we are not required to have feelings of loss. However, there is an unsettling dissonance between the fictive and real. Walking around the diminutive disaster, you sense the physicality of the damage, while also enjoying the power of art to contain chaos. There is a conflict between our emotional connection with the real sense of danger and our being entertained by the beauty and charm of the tiny, broken objects. The crumpled pieces of metal and tangled carousel animals are at once horrific and fascinating.

Krammes culls images, texts, music, and any other event or experience that he comes across in his preparation for a work, and the objects he creates reflect this searching process. Of Calamities builds a relationship between the piece and the old photograph. The carousel is a cultural symbol of youth and innocence; damage to the representative object redounds to its larger counterpart. When viewed as a simulation (in Baudrillard’s sense), the miniature carousel begins to elide the differences between the real and its copy, opening up another layer of meaning. The miniature’s double existence generates a dialogue between the effects of nature’s catastrophic power and the safe, ordered structure of childhood. It is as if the safety of childhood has spun out of control. By presenting the viewer with the evidence of a hurricane, Krammes has overlaid a more chaotic kind of circular motion onto the safe and sedate motion of the merry-go-round—the confusion of adolescence overtaking the security of childhood. The piece becomes a mental and emotional doorway through which the chaos of nature and the carousel (a childhood symbol for joy, which by adulthood degrades into cliché) transform and blend, reshaping our sense of both.

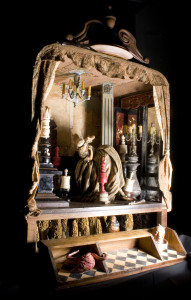

PLATE 1. Barry Krammes. Of the Peculiar, 2007. 30 x 19 x 13 inches. Mixed media. Photos: Charity Highley.

Like Christian altarpieces, Krammes’s objects rely on narrative. However, the stories Krammes weaves through his works offer only faint traces of familiar characters and circumstances. Recognizable elements surface like ghostly apparitions but never fully materialize. The narratives come to us peripherally, through metaphor and allegory. Historically, Christian altarpieces and reredos presented clear stories based on a universally accepted code of images and topics from the Bible and the lives of the saints. Krammes’s works are more ambiguous in meaning, derived from partially deconstructed objects that reverberate with stories and archetypes of the past. In Of the Peculiar (2007), vestiges of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-glass (mirror, teapot, chess pieces) reside in a room occupied by a miniature wax woman, who is placed as if shying away from her mirror image [see Plate 1]. With so many elements of the Alice story in one room, they begin to empty themselves of their original meaning, becoming ready for reinterpretation. The figure is doubly shrunken, both as a miniature and in her shrinking gesture [see Plate 5]. She conveys an anxiety that resonates both with the Alice story and larger questions of being. These kinds of inferences happen freely within Krammes’s works. He builds intricate relationships, shifting among different source materials, resulting in what he calls “an insanely intricate puzzle.”

There are never absolute solutions to Krammes’s puzzles, only open associations which are left for the viewer to edit. In this sense, looking at a Krammes piece requires an active mode of contemplation. The suggestive cultural references alternately blend with and are absorbed by the viewer’s own inferences and connections. Objects serve to elicit memories which then become partnered with the cultural signs that Krammes has deftly included.

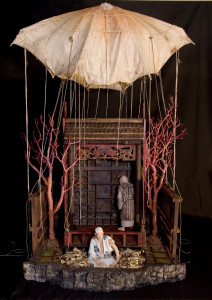

PLATE 2. Barry Krammes. Of Floating Worlds, 2007. 49 x 38 x 15 inches. Mixed media with lights. Photos: Charity Highley.

As its title implies, Of Floating Worlds draws on the Japanese tradition of ukiyo-e, or “floating world” prints of the Edo period (the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries), art that depicted an ephemeral world of fantasy and desire [see Plate 2]. While the title and elements of the scene hint at the Edo period, the use of figures costumed in imperial Chinese garb deny any direct reference to the ukiyo-e [see Plate 6]. This ambivalence toward historical accuracy is a deliberate move on Krammes’s part and serves to forestall any purely cultural reading. The artist quotes facilely from a surreal parade of images. The bright colors and festive figures descending the pavilion steps provide a welcome levity. However, Krammes continues to walk a narrow line between the familiar and the strange, between the comfortable and the underlying fears and doubts we keep at bay. The piece is set up as an entrance or gateway, a frame for multiple activities. Life-sized wooden hands emerge behind it, a dramatic contrast of scale with the narrative inside. Like a puppeteer’s, they seem to be pulling on invisible threads, as if to animate the scene’s activity. This contrast between the tiny crowd and the Godlike hands offers an image of the unseen. Krammes’s work is full of such hints of hidden presence, but he never fully reveals his intentions or explains the motives behind the placement of objects. We are left to draw conclusions on our own, revealing more about ourselves than we learn about the artist. Krammes’s work brings us closer to our own sense of the world by making us more conscious of the way we see.

Like the makers of Christian altarpieces, Krammes emphasizes the power of looking. Traditionally, an altarpiece was meant to comfort the viewer in present sufferings and hold out the promise of a heavenly future. It extrapolates the meaning of the altar itself, a sign of Christ’s sacrifice. This function depends upon the viewer’s regard for the object as a source of power. This analysis may sound postmodern, but there is a timeless significance in the way the faith of the believer makes the object meaningful. In effect, it is the believing viewer who finalizes the altarpiece’s importance and defines it.

The primacy of the relationship between viewer and altarpiece finds a surprising echo in the art theory of Marcel Duchamp, the father of conceptual art. Duchamp’s works challenged prevailing definitions, pushing art practice beyond high modernism and into the postmodern era. For Duchamp, the creative act is unfinished until the viewer has received it. Just as the effect of an altarpiece depends upon the faith of the worshipper, secular art also requires a kind of faith. Nor did Duchamp shy from using religious language to describe the viewer’s experience. He wrote:

The creative act takes another aspect when the spectator experiences the phenomenon of transmutation; through the change from inert matter into a work of art, an actual transubstantiation has taken place, and the role of the spectator is to determine the weight of the work on an aesthetic scale.

In other words, it is the spectator’s willingness to view a thing as art that makes art of it.

Most relevant to Krammes here is the centrality of the viewer’s gaze. His works lead us through a process of contemplative looking as the final step in creating the art object. In Krammes’s assemblages, as in altarpieces, the act of contemplation transforms the object and the viewer together. Altarpiece and art object both draw on the action of faith. In Krammes’s work, the act of looking is a detached one rather than one of devotion; it may begin as mere spectatorship or even voyeurism, but as we gaze, our passive looking leads to active contemplation. The work draws us in. Perhaps it is appropriate in our postmodern circumstance that the initial, oblique kind of viewing becomes the road to something more meditative and personal.

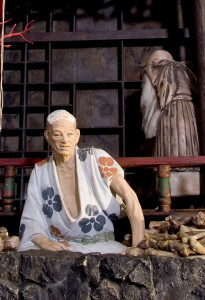

Krammes’s works often set forth an intricate relationship between contemplative figures and others who secretively gaze at or spy on them. In Of Longing and Of Floating Worlds, the spies stand outside the theater on a sort of proscenium; they are outside, looking in, as are we. Because the works are arranged so that the onlookers share our line of sight, we identify with them. Since neither we nor the spying figures can access the thoughts of the meditative central figures, our gaze is piqued. We long to see into the mystery. Suggestive of an Asian bathhouse, Of Longing shows a servant figure facing what appears to be an opaque shoji screen door [see Plate 3]. He is turned away from the center stage, where a seated figure faces outward, his face serene but closed [see Plate 7]. As the title suggests, the inaccessibility of the central figure creates a sense of desire; like the servant, we yearn to know the thoughts of the central figure, but we face a closed door. Of Floating Worlds creates a similar dynamic. Here, peasants spy into the room where a courtly figure studies a life-size landscape painting. The festive procession marches out of the pavilion toward the viewer. They, too, seem to be in on the secret, having just seen the painting inside. The spying figures create an unresolved tension, echoing and highlighting the manner in which we peer into this mysterious otherworld.

In Of the Peculiar, we viewers have no such avatars within the tableau, no intermediary between us and the central figure. We view her in profile as she confronts her own reflection. Startled by her mirror image, she throws up her hands to shield her view, a dramatic gesture suggestive of self-doubt. Beneath this upper room is a fairytale basement space containing a forest of mushrooms and a dwarf, a counterpoint that makes the scene upstairs even stranger. With these two rooms, Of the Peculiar lays out a map of anxiety: the alarmed figure performs the fear of that which she cannot see—literally and metaphorically, of what lies beneath.

Krammes’s collections of found and antique objects have what Walter Benjamin described as aura. They generate a sort of eerie, numinous power by the sheer amount of age and use that is seen and felt in the object. In their nicks, tears, rust, and worn paint, these objects bear the marks of their previous owners and uses. The many hands that have held and exchanged them have left stains, giving the objects an accumulated sense of life and deepening the meaning of the total piece. These objects vacillate between what they were originally made to be (a doll, a teacup) and the new roles they play in Krammes’s fantasy creations. In these theatrical, constructed worlds, the wishes and dreams of inanimate things come alive; the mundane and banal are allowed a chance at something greater. A new kind of life, a new essence emerges, one that is only possible within the artist’s world.

Krammes’s practice of poetic recycling is central to the spiritual dimension of his work. Here the broken and the wasted are remade into forms that, while not practical or useful, go beyond the objects’ intended purpose. A shepherd of used things, Krammes gathers and arranges them into tableaux that give them new meaning. Tiny chairs and drawers become persons; a broken and rusted lamp stand becomes the core of a carousel; the innards of an old umbrella serve as the frame for a balloon kite. That Krammes so often makes use of broken, cast-off objects is part of the Christian resonance of his work: before these objects can be filled with new meaning, they have to be emptied out, broken down, and abandoned, so that their pain and loss can be reconfigured through a kind of grace.

A more sophisticated example of Christian resonance is Krammes’s treatment of the wax woman in Of the Peculiar. Christlike, the body of the Alice figure bears the wounds and markings of history. Several threads come together here: the gospel narrative, the looking-glass world story, and the allegory of doubt and self-preservation (in the drawing back from the mirror). Krammes’s poetic salvage process imbues recycled objects with stories rooted in archetype and in the biblical past, remaking them into foundations for elaborate theater. Here, the scarred central figurine is the centerpiece that holds together all the narrative layers.

In another Christian echo, Krammes’s objects are arranged without any sense of hierarchy or consideration of monetary value. Here, the last shall be first and the first shall be last. Precious antiques are jumbled together with cast-off junk, and no object is spared for the sake of preservation. Krammes may collect valuable objects for years, such as his carousel figures, and then subject them to ruination if he feels the piece requires it. This sense of sacrifice, together with the object’s uncanny aura, often gives Krammes’s work a sacred feeling. While not overtly spiritual or Christian, works such as Of the Peculiar, Of Longing, and Of Floating Worlds, with their play on the frailties and passages of human life, have a religious resonance. One of Krammes’s colleagues once likened them to the morality plays of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, which focused on man’s struggle with sin and his eventual attainment of godliness. While vestiges of this old form do inhabit his tableaux, Krammes loosens the meaning. The viewer never arrives at a complete, obvious lesson. A figure shrinks from a mirror or looks longingly at a painting: there are hints of moral struggle, but nothing absolute or didactic. Some dissonance always keeps the suggested narrative uneven: a festive atmosphere surrounded by large, godlike hands resists any easy read. Krammes’s mode is thoroughly postmodern, but a lingering sense of Christian meaning is always part of the carnival. His admixture invites the viewer to participate in a thinking journey, where discoveries are left for her to make rather than imparted to her.

As he gathers his miniature antiques and cast-offs, Krammes is collecting from the wasteland of cultural meaning. He takes objects that have been damaged or degraded over time, whose meaning has eroded, and further deconstructs them by placing them in settings that contradict their intended functions. As we study his tableaux, we simultaneously see the discarded object for what it was and for what Krammes has made of it. This constant shifting and refocusing creates an active contemplation, making us aware of ourselves even as we look into fictive, theatrical spaces. The process of looking becomes an exploration that constantly reminds us of our own presence.

At the core of Krammes’s practice is the allure of the miniature. He draws us in by the familiarity and strangeness of the tiny objects. They entice us to look further into his creations, ensnaring us by their similarity to the real world while they act out fantastic analogies.

While Krammes views his work as assemblage, this recent series has evolved past that tradition. Assemblage creates meaning through the personal, unconscious association of juxtaposed objects. In using objects for the sake of their discarded cultural significance, Krammes is drawing on a broader art-historical lineage. Like Duchamp before him, he makes the conceptual move of redefining objects by placing them in a new context, but nearly a century later, Krammes is working in a different era, in a cultural landscape that is less coherent and more fluid.

Postmodernity is often reviled for the ways it has emptied art of meaning and left us alone with the cynical and clever, but it has also freed art practice to go beyond intended meanings and opened up new ways to play with narratives. Through such a renovation, Krammes is able to draw meaning from sources that seemed to have dried up long ago. Like the man sitting on the pile of bones in Of Longing, Krammes has gathered about him the remains of our past. These discarded objects have a unique ability to tell us the truth: their old cultural meaning has been stripped away, leaving them bare. Like the prophet Ezekiel in the desert valley, Krammes can speak to these bones, reanimate them, and hear and interpret their message. These cast-off shards reveal what has always been within us: doubt and faith, the profane and the sacred, fear and hope. In Of Longing, a balloon kite (made of a cast-off umbrella) hovers above the scene on strings, as if the piece longs to float up into the air. In Krammes’s world, even the broken and forgotten inhabitants of the postmodern cultural wasteland are alive with a tenacious hope.