On Looking at Jila Peacock’s Ten Poems from Hafez

The book Ten Poems from Hafez includes Jila Peacock’s calligraphy and new translations from the Persian. A limited handprint edition, with silkscreens on Japanese paper, was published in 2004 and is in the collections of the British Museum and the National Library of Scotland. A paperback version is published by Sylph Editions (www.sylpheditions.com).

IN THE MIDDLE EAST, calligraphy is considered the highest of the arts. The Far East, too, despite its glorious tradition of landscape painting, ranks calligraphy high above it. Contemporary artists in these nations are experimenting with their cultural legacies, and nowhere is this more brilliantly and beautifully practiced than in the calligraphic word-pictures of Jila Peacock. Peacock is an Iranian, born there, but taken to Britain as a child, and both languages seem native to her. She studied medicine in London; she also studied art, at the famous Saint Martins School. Both these arts she now practices in Glasgow, and has added a third, the art of translation.

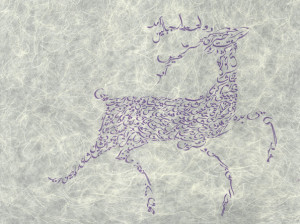

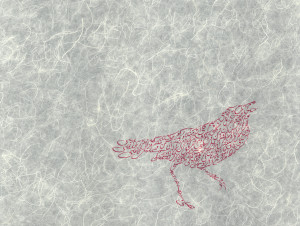

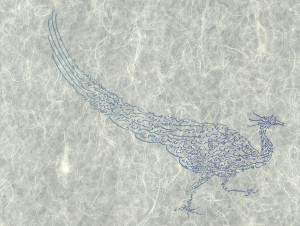

The great Iranian national poet is Hafez, whose influence pervades their culture even more than Shakespeare does our own. He lived earlier than Shakespeare, though, a contemporary of Chaucer and Dante, and of equal stature. Peacock has deepened her understanding of this poet by translating him. And she has gone further: she has chosen ten poems in which some animal is significant and—refining and perfecting an old Persian skill—created an image of the bird, fish, mammal, or insect using only the words of the Hafez poem. The letters are written in glorious Persian calligraphy: swirls, plenitudes, and crescendos creating a complexity that to an Iranian is both legible and lyrical. An outsider cannot read the calligraphy, only respond to it.

Hafez was probably a Sufi. One has to say probably because our only certain biographical fact is that his name is not a birth name but an honorary title, bestowed on one who could recite the holy Koran from memory in its entirety. He is a mystical poet (hence the likelihood that he was a Sufi of sorts—mystics all), and his theme is love. The love he writes about can be taken on several levels, rather as in the biblical Song of Songs, where divine and human love are one. Hafez describes the intoxication of wine and of prayer in ambivalent terms: the lower points to and rejoices in the higher [see Plate 7].

§

Look at Peacock’s Horse [see Plate 8], with its proud and noble head, its elegant legs, almost dancing with delight in life, its ears pricked for sound. The poem refers to the nightingale, the bulbul, and (as an example of her wit) the calligraphic signs for bulbul form the peaked curve of its two ears, cleverly communicating that this high-stepping creature listens to the nightingale while we watch. Peacock also draws the nightingale itself [see Plate 9], trembling with passionate song, which the calligraphy renders with delicate emotion while the parted beak pours forth “a mournful trill,” in which “surged all his grief.” Traditionally a nightingale is a symbol of intense love, felt by the bird for the rose. For the Sufi, the yearning soul is the nightingale, God himself the rose. Peacock’s nightingale quivers with longing for the beloved, as does the poet. The horse too is a love image, and the spiritual significance is for us westerners perhaps deepened by our inability to decipher the Persian script of the ghazal, the love poem.

The meaning becomes for us, literally, incomprehensible, as are all divine mysteries. Peacock uses nasta’liq script, the most intricate of all Persian calligraphies, and she uses different colored pigments for her individual works. She is known as a colorist, but here she has confined herself in each case to a single tone: deepest green, silver, or florescent pink, with perhaps just one dab of a contrasting color, as in the bright red beak of the emerald parrot. The color is not arbitrary; in each case it is part of the total artwork. The butterfly, for example, glowing on the page, seems to shimmer in a luminous lift-off, so alive are its outstretched wings, each a mirror image of the other. The pure beauty of the poetry is also essential to the full effect of the word-form. The peacock, a work of stately magnificence, is composed of a longing lament that begins (at the bird’s beak in Persian, which reads right to left) with a “yearning heart,” “existence” become “an illusion” because all reality is in the beloved who is absent [see Plate 10]. Toward the close Hafez writes:

Your shadow falls across my frame,

Like the breath of Jesus over withered bones.

We may stop, amazed, yet Islam has always honored Jesus—not, it is true, as the son of God, but as holy prophet. Jesus in Arabic is Ruh Allah, which means “spirit of God,” the spirit (or breath) that raises the dead. The lovely inclusiveness of Islam, last historically of the three great religions, makes pitiful nonsense of political antagonism, just as Christianity’s reverence for the Jewish Bible emphasizes the shame of anti-Semitism in so-called Christians.

These works of profound seriousness and love, where meaning and image are married, and the love of God, which is love itself celebrated, are pure gift to our sad world. We have the happy responsibility of responding to them. In reading the poems, so sensitively translated, we are drawn into the beauty of the calligraphic form, and in responding to the calligraphy, we come nearer to the mystical truth of the poems.

O Hafez, rejoicing in the beauty of your pen,

We pass your precious words from heart to heart.

§

When I wrote The Story of Painting, I spoke only of western painting, the whole lovely progression from Giotto to the present. Was I subconsciously afraid of eastern painting? At the conscious level, it never entered my mind. But later, through a dawning love for ceramics, above all for the great Sung bowls and the Tang tomb figures, I gained courage to explore what I belatedly realized is the greatest artistic tradition in the known world. Again, it is the early art that fascinates me. (That “early” is a relative term in China; they have works of majesty predating the pyramids.)

But it was not my love for eastern art that drew me to the work of Jila Peacock. Rather, it was my ever-growing love for another art form, again one I had unfairly neglected in my rash art-historical youth. This is the art of the icon, especially the sixth and seventh-century icons (few in number after the years of iconoclasm). It seems to me that Peacock’s infinitely skillful calligraphy, as she spells out the lyrics of this mystic poet, has its rise in the same silence and prayer that are essential for the creation of an icon. It is the attitude that makes a work religiously iconic, not the actual religion, though of course the incarnation of Christ, the bodily form taken by the divine, is the validation of the icon painters’ reverent attempts to make God visible, to unite the praying heart with what is pictured. Peacock does something of the same, I think. Hafez yearns toward his God, and these word-forms are to his glory.

Khwajeh Shams al-Din Muhammad Hafez-e Shirazi

Plate 1. Jila Peacock. Fish, 2005. Ink on Paper. All images from the book Ten Poems of Hafez © Jila Peacock.

Fish

When my beloved offers the cup

Graven idols are crushed,

And those who gaze into that intoxicating eye

Call ecstatically for rescue.

I plunge into that ocean like a fish

Craving the beloved’s hook,

I fall pleading at those feet

In hope of a helping hand.

Happy the heart who like Hafez

Is drunk with the wine of creation.

All translations by Jila Peacock.

Deer

Dawn’s bright awakening to my pillow called:

“Arise, your sweet Prince is come.

Drain the cup and swaying see

How your lover manifest is come.

Rejoice you lonely seeker of the scented path

For out of the wilderness the perfumed deer is come.”

Sweet tears shall soothe the burning cheeks again

And sighs comfort the cries of unrequited lovers.

The bird in my heart with glory soars afresh

Tremble poor pigeon for the falcon is come.

Take comfort in the cup and banish fear of friend or foe

For the last has fled and the first is come.

The clouds of spring look down on these troubled times

While tearful rains deliver daffodil and rose.

And hearing songs of Hafez from the nightingale

The scented zephyr, revelling, is come.

Nightingale

Roaming the dawn garden to gather flowers,

I heard the cry of a nightingale.

Forlorn like me he loved the rose,

And in that mournful trill surged all his grief.

I wandered in the garden’s timeless moment,

Balancing the plight of rose and bird.

For the rose is the heart of beauty,

And the nightingale, beauty’s slave;

The first may show no favor,

The second seeks no change.

So stirring was his passionate song

That I was moved beyond endurance;

For endless roses flower each day,

Yet no man plucks a single bloom

Without the risk of thorn.

O Hafez, seek no gain from the orbit of this wheel,

It has a thousand pitfalls and no respect for you.

Peacock

Until your hair falls through the fingers of the breeze,

My yearning heart lies torn apart with grief.

Black as sorcery, your magic eyes

Render this existence an illusion.

The dusky mole encircled by your curls,

Is like the ink-drop falling in the curve of J,

And wafting tresses in the perfect garden of your face,

Drop like a peacock falling into paradise.

My soul searches for the comfort of a glance,

Light as the dust arising from your path.

Unlike the dust, this earthly body stumbles,

Failing at your threshold, falling fast.

Your shadow falls across my frame,

Like the breath of Jesus over withered bones.

And those who turn to Mecca as their only haven,

Now at the knowledge of your lips tumble at the tavern door.

O precious love, the suffering of your absence and lost Hafez

Fell and fused together with the ancient pact.