A fuller version of this essay appears in the catalogue for The Word on the Street: The Photographs of Larry Racioppo, an exhibition shown at the Museum of Biblical Art in New York in the summer of 2006.

ON A CORNER in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, across the street from Saint Anselm’s Church, is a parking lot. At its entrance stands a small shed just large enough to shelter the man who attends to the parishioners’ cars. The shed’s white-painted plywood walls have been carefully covered with all manner of decoration: tinsel garlands outline the door and its canopy; an American flag and a pow-mia banner are prominently displayed; strings of white twinkle-lights are attached to the roof; and colored Christmas lights are strung on the sides. An electrified Christmas star hangs like a wreath on the shed’s door, framing a photograph of the late Pope John Paul II. A plastic rosary dangles over the pope’s portrait, and a simple wooden cross is nailed to the shed’s peaked asphalt-shingle roof. Pulling open the front door reveals the true scale of the attendant’s attention: the walls and ceiling are completely papered over with sacred imagery and personal mementos. Deliberate care and intention over time have transformed a diminutive plywood structure into a jewel-like shrine. Its textures, details, intimacy, and, conversely, the monumentality of the attendant’s efforts are honestly yet artfully communicated in Joe Pezza’s Parking Lot Shed, a pair of large-format photographs by Larry Racioppo.

For more than three decades, Larry Racioppo has captured religious imagery that is part of the fabric of New York City. The Word on the Street: The Photographs of Larry Racioppo, which ran this summer at the Museum of Biblical Art in Manhattan, featured more than seventy-five of these photos, many on view for the first time.

A New Yorker born and bred, Racioppo began photographing in the city in the early 1970s. Initially focusing close to home in his south Brooklyn neighborhood, Racioppo photographed his family and immediate environs, capturing the happenings of everyday life. Using a hand-held camera, he shot street scenes, vignettes from the homes of his parents and aunts, and, among other things, children in Halloween costumes. This last series, which he began in 1972, culminated in the book Halloween, published by Scribner in 1980. Racioppo never deliberately chose religion as a subject; he simply shot what he saw around him, photographing his first Good Friday procession in 1974 in his childhood parish, Saint John the Evangelist in Brooklyn. During this time he also began to focus on his family’s Catholic practices, photographing the instances of private devotion that were part of their daily lives.

Beginning in the 1980s, Racioppo began to broaden his geographic range, photographing outside of his immediate neighborhood while continuing to focus on public and private displays of devotion. By the 1990s, Racioppo says, the themes of “Brooklyn, Italian, Catholic kept coming back in one form or another.” He started photographing more Brooklyn neighborhood church processions, Catholic and otherwise. His subjects have included the Good Friday procession at Saint Barbara’s Church in Bushwick and the musical drama At Calvary, sponsored by the Greater Mount Zion Shiloh Baptist Church of Fulton Street. In 1998, Racioppo began to photograph the Giglio festival and the feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel in Williamsburg. Returning over the years to catch the Giglio from multiple perspectives, Racioppo has photographed the procession from rooftops, from homes lining the streets through which it passes, and from the point of view of the confraternity members who carry the floats.

Sensitized to religious imagery during his childhood, Racioppo photographs parish and private rituals—as well as Christian iconography throughout the city of New York. Eighty-one of these photos were collected in the recent mobia show. Far from a systematic survey, the exhibition captures imagery as the photographer finds it. The photos are taken from all five boroughs and include murals, small businesses, tattoos, and private shrines in homes and yards.

Using small, medium, and large-format cameras, both hand-held and stationary, he calibrates the size of the print to the subject at hand. Favoring crisp detail that does not soften when enlarged, he uses medium and large-format cameras whenever possible. The bulky large-format cameras, which produce 4-by-5 and 8-by-10-inch negatives, have to be carted around the city in a trunk. Racioppo often photographs his subjects over an extended period of time and using various cameras. With many murals, he first takes a “for the record” shot using a small hand-held, carefully noting the location and conditions of the site. He later returns with a large-format or panoramic camera, which allows a photographer maximum control. A view camera also ensures that the large prints will have the depth of field and clarity of detail.

Racioppo finds many of his subjects through his work as the official staff photographer for the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development. Since 1989, he has recorded the city’s housing rehabilitation efforts, work that has taken him to some of the city’s most distressed neighborhoods, where abandoned housing awaits redevelopment. Photographing building sites for his job, Racioppo was struck by the religious expression that surrounded him, in particular by the huge memorial walls that mark the loss of a loved one. He marveled at their genuine and pious devotion.

In photographing these street memorials, Racioppo achieves great poignancy. The memorials range widely in media, from a simple wooden cross on a Queens underpass to graffiti carved into drying concrete to a whole series of spray-painted murals. These memorials bring mourning into the public sphere, each bearing witness to a great loss.

In the case of the laboriously painted murals, Racioppo’s large-format photographs successfully capture the saturated colors and rich textures of these often over-life-size paintings. The murals are ephemeral, the walls likely to be painted over or torn down within a few years, and the photographic form underscores that loss, while making a permanent record of what was there. The artists draw from images of western art history: Christ crowned with thorns, the Immaculate Heart of Mary, the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the hands of God and Adam from Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel fresco, the Pietà, and the saints. Other photographers and writers have noticed this pattern, too, most notably Martha Cooper and Joseph Sciorra, who surveyed the development of the spray-painted memorial in New York City from 1988 to 1993. In their groundbreaking photo-documentary work, RIP: New York Spraycan Memorials, Sciorra noted that many of the iconic images that appear in these murals are the same ones found on the small remembrance cards handed out at funerals, on holy cards, and on devotional calendars, all of which are part of the daily lives of many Latino Catholics. Sciorra linked this imagery to the cultural context of the memorials, noting that Latino artists “play[ed] a predominant role in the development of the New York memorial tradition.” He also observed that the development of a memorial is tied to the wishes and religious predispositions of the family and friends commissioning it—so it’s no surprise to find funeral and holy-card iconography on the walls of Brooklyn and Bronx neighborhoods.

Many present hybridized iconographies that draw on both classical and modern images. The mural he photographed for In Memory of Mike appealed to Racioppo in a very personal way. It includes a representation of the archangel Michael, the name saint of both the dead man and the photographer’s late cousin. Using a large-format stationary camera, Racioppo was able to pick up textures and saturated colors not necessarily visible to the naked eye. The mural features a standard depiction of Saint Michael slaying a winged demon, his wings outstretched, his sword raised in his right hand. In his left, he holds the perfectly balanced golden scales of justice. Like all commemorative works, In Memory of Mike presents an idealization of the deceased, including secular symbols of what he loved in life: beneath Saint Michael are a BMW coupe and what looks like a 7-series sedan, along with a dedication from the man’s wife and four children. Racioppo has photographed similar iconographical admixtures as part of what he calls his “sacred and profane” series.

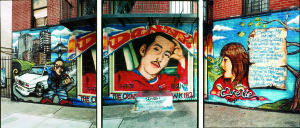

Plate 1. Larry Racioppo. Danny and Evette RIP Triptych, 1998. West 182nd Street and Walton Avenue, the Bronx. 24 X 20 inches. 6 X 5 color negative.

A superb example is the Danny and Evette RIP Triptych [see Plate 1]. This mural personalizes the memorial by localizing it in a specific part of the city. The first panel depicts the status and power that Danny presumably commanded in his Bronx neighborhood. Looking tough and menacingly territorial, he stands in front of an expensive SUV that comes to a screeching halt, a cigar (most likely a blunt, a marijuana-packed cigar) in his mouth. Brow furrowed, he holds a fistful of money against the backdrop of a stylized skyline featuring the George Washington Bridge. The triptych’s central panel is a gentler, more intimate portrait of Danny with the dates of his birth and death. The third panel shows the profile of a woman named Evette, probably Danny’s girlfriend or wife and now companion in death (under her name appear the letters RIP). Evette mouths words that are inscribed on a large scroll unfurled beside her:

Don’t cry my love ones (sic). I am reunited with God, I’ll be waiting for you in heaven. I die but my love doesn’t die. I will love you in heaven as much as I loved you on earth.

To everyone that loved me I ask you to pray for me. That’s the only proof to show me your feelings toward me.

Fortunately, Racioppo photographed this elaborate mural in 1998 before it was painted over.

Although the hybridized imagery of the memorial mural is often quite beautiful, one can’t escape a sense of discomfort: many of these tributes glorify the culture of violence and drugs that cut short the lives of those they commemorate. Sciorra concludes that many of the memorials “offer testimony to the violent deaths of Latinos and African Americans brought about by the unchecked proliferation of guns and drugs. The walls are implicit critiques of the social inequities of hardcore poverty, pervasive racism, and official neglect.”

The hybridization of imagery takes various forms. Perhaps most striking are the memorials that portray the deceased in divine settings. In several photos, Racioppo heightens the monumentality of the figures by focusing tightly in on an individual portrait within a larger mural. In RIP Kenny, a life-sized young man clad in blue, his arms outstretched, sports a large gold cross around his neck (sacred “bling”?) and a black pager on his belt loop. A halo encircles his head, and his body is surrounded by a mandorla of golden flames. His posture suggests nothing short of a crucifixion, a martyrdom, an interpretation reinforced by the shrine (devotional candles and a small statue in an octagonal Plexiglas box) positioned at the figure’s feet.

Several memorials depict the deceased as angels doing in heaven what they did best on earth. In karlton, a young, athletic man runs down a serpentine path dribbling the planet earth like a basketball. This portrait is remarkable for its specificity and naturalism, as well as for its seamless blending of sacred and secular iconography: the basketball uniform with the number 23 (Michael Jordan’s when he played for the Chicago Bulls); the large, downy wings and floating halo; and heaven’s pearly gates in the background. The angelic Karlton’s joy, finesse, and skill make him a sort of youthful, urban, American version of the Salvator Mundi (iconography in which Christ, his right hand raised in blessing, holds in his left an orb that symbolizes the earth). Another work, Crazy Legs, shows the deceased as an angelic DJ spinning records in heaven. A halo encircles his knit cap, and his wings are tensely drawn in at his sides, echoing the expression of concentration suggested by his pursed lips and closed eyes.

In Loving Memory Pietà preserves the work of an artist who has drawn from the classic iconography of the Pietà, that timeless image of loss. Although this memorial could be read as a standard Pietà—Mary clad in her traditional blue mantle, holding the still supple body of her lifeless son—a subtle detail suggests that it is anything but. Against Mary’s blue skirt, in the hand of the dead man laid out on her lap, is a glowing yellow spray-paint can. The detail suggests that this Pietà is being used as a visual metaphor for a more personal grief. Perhaps the loved ones who commissioned the memorial hoped that the dead man—George Torres—has found comfort in Mary’s arms. Read as a visual metaphor, the man Mary mourns could well be not Christ but George Torres, who was likely a graffiti artist or tagger. If the dead man is indeed Christ, the spray can ties Torres’s suffering and death with Christ’s own.

Another group of Racioppo’s photos, taken primarily in Brooklyn and Manhattan, focuses on images of devotion in the workplace. He finds many of these subjects by happenstance. From his car, in restaurant kitchens, at delis and pizzerias, Racioppo has developed an acute awareness of the devotional imagery in unlikely places.

Religious iconography is unmistakably present in Racioppo photographs. What a casual customer might overlook is brought front and center, made immediate. In Casanova Pizzeria Counterman, the anonymous counterman, his sleeves rolled to the shoulders, is framed in the center of the shot. To the left is the marble countertop used for making dough; to the right, another counter holds trays, a soda fountain, coffee urns, and other miscellany of food service. In the background are the pizza ovens, often heated in excess of five hundred degrees. At the very center of the frame, extending the entire length of the man’s upper arm, is a large, exquisitely inked tattoo of the Virgin of Guadalupe. The virgin, dressed in her characteristic red robe and blue mantle, is surrounded by the traditional mandorla, and the whole is set over an image of the cross, which stretches from the counterman’s elbow up and over the curve of his shoulder. The tattoo’s deeply saturated colors stand out against the beige and steel tones that predominate in the photograph. Furthermore, the red of the virgin’s robe picks up spots of red in the broad middle ground, such as a “No Smoking” sign, the marinara sauce on the pizza slices on the counter, the counterman’s scarlet baseball cap, and plastic trays and various food industry logos. The centrality of the tattoo within the larger composition makes it clear that Casanova Pizzeria Counterman celebrates the Virgin of Guadalupe, and not pizza.

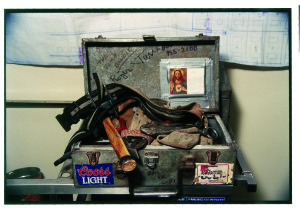

Plate 2. Larry Racioppo. Tin Knocker’s Toolbox, 1995. Gold Street, Manhattan. 16 X 20 inches. 35 millimeter color negative.

This and other photos of devotion at work capture the seamless integration of people’s belief into their daily lives: A holy card duct-taped inside the lid of a cluttered steel toolbox—along with beer stickers and the remnants of an ID badge—suggests a small, private devotional shrine [see Plate 2]. A hair salon, photographed in crisp detail with a wide-angle lens, is also a sacred gallery filled with a sumptuous abundance of Byzantine icons, Old Master paintings of the virgin and child, and images of saints. At the Cristo Rey Barber Shop, barbers and clients stolidly go about their business beneath signs proclaiming “Trust in the Lord” and “God is Love.”

Taken during Lent, Bread Cross shows the transformation of an everyday staple into a symbol of faith—an advertisement in the broadest sense. Braided and shaped into the form of a cross, the loaf sits in the bakery’s front window, a symbol of the season clearly visible from the street. Racioppo underscores its prominence by angling his camera in order to capture the texture and detail of the bread in what would otherwise be a portrait of a rather dull, if functional, bakery window. He finds similar declarations at a garage, a deli, and an iron workshop. Racioppo’s skill in framing his subjects, isolating them within the larger streetscape, draws our attention to markers of devotion that could otherwise disappear.

More recently, Racioppo has turned his attention to examples of wearable devotion that he comes upon all over the city—tattoos, T-shirts, and even jewelry. Taken in Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens, this new group of photographs shows the deeply personal ways in which people broadcast their faith.

T-shirt Triptych is composed of three 2005 Brooklyn photographs of shirts adorned with, respectively, image, word, and both image and word: the Virgin of Guadalupe, the text of John 3:16, and the Sacred Heart of Jesus with the motto “Jesus is my homeboy.” The first two panels show only the back of the shirts—the subject is the imagery printed on the tees, not the people wearing them, who remain anonymous and depersonalized. The third panel, a portrait, is as much about the man wearing the shirt as the image printed on it. In crisp detail, the photograph reveals how the decal of Jesus has faded and cracked over the years with repeated wearing and washing—the telltale sign of a favorite tee. The texture of the photograph becomes a metaphor for personalization. Surrounded by a crowd, the man is a witness for his faith. Opening his military-style camouflage jacket, he reveals an image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus; the man is making the same gesture as the Jesus on his shirt, who pulls back his robe to reveal his own heart. Crowned with flames, the tiny heart is positioned at the same relative spot on the torsos of both the man and his Savior. Together, the two of them bear the Good News. Their bond extends to the shared leftward tilts of their heads, Jesus gazing upward as if to catch a glimpse of the man sporting his likeness.

During his travels around the city, Racioppo has been fascinated by the pious sentiments, petitions, admonitions, and warnings he finds drawn, painted, and assembled quite literally everywhere (and on everything) on the street. The sometimes strange biblical phrases and prophetic statements are irresistibly compelling to him.

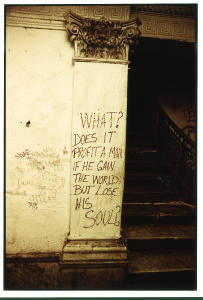

Plate 3. Larry Racioppo. Lobby Message, 1992. Saint Nicholas Avenue near West 116th Street, Manhattan. 24 X 20 inches. 35 millimeter black-and-white negative.

Some, like Lobby Message [see Plate 3] are hastily, almost desperately scrawled. Others are meticulously painted and simply phrased. (“Insurance by man is limited. Insurance by Jesus is eternal,” reads one sign on a cinder-block wall.) Racioppo also turns his lens to more deliberately crafted assemblages like Jesus My Fire Escape [see front cover] a work that carries particular significance for him: “As a city person, all the desert imagery in the Bible had no real meaning. Who ever saw a shepherd? But a fire escape—for a city kid, this has meaning,” Racioppo says. Despite the range of forms and sentiments these public declarations take, each reflects the universal desire of authors and artists to be noticed, to be heard—a desire that Racioppo’s lens satisfies.

Plate 4. Larry Racioppo. Statue of Liberty Pietà, 2005. Atlantic Avenue near Troy

Avenue, Brooklyn. 30 X 20 inches. 6 X 9 color negative.

For Racioppo, the “word” on the street also refers to instances of religious imagery. In Statue of Liberty Pietà, a weatherworn print of the Statue of Liberty cradling a dead man on her lap is framed within a steel support column for the elevated train [see Plate 4]. (mobia curator of education Dolores DeStefano later discovered that this image was a protest poster made in 2004 during the Republican National Convention in New York City.) The body cradled by the statue is draped with an American flag. The image is instantly recognizable as an homage to Michelangelo’s famous Pietà. Using a medium-format camera, Racioppo captures the creasing and peeling of the paper and paint and the residue of a dried liquid, something thrown or splashed, running down the center of the beam. Set in the darkened hollow of the beam and lit by the bright summer daylight that falls on the strips of steel that flank it, the print is a small beacon of sorrow and compassion, a sort of spiritual handbill gracing a busy Brooklyn street.

The Sin of the World is a bold admonition against the culture of drugs and violence in many of America’s urban neighborhoods (and which a number of the memorial murals discussed above also witness to). Using a Widelux camera, Racioppo captures the mural in its entirety, emphasizing the prominence of the central figure of Christ by using the camera’s swing lens. The photograph has a convex appearance, the result of the photographer deliberately positioning himself directly at the center of the mural and at close range. The muralists depict a suffering Christ, who bears the world’s cross on his shoulders under the legend “Enough Blood Shed.” To the left is a terrifying scene that could be called a modern-day ascent into hell: a fierce, green, alienlike devil bares his fangs as he pulls one of the damned by his ankles up into hell’s window (the muralists have cleverly incorporated the frame and sill of a bricked-up window into the design). The damned man’s crime is signaled by the grotesquely oversized crack vials which fall aside as he is dragged to perdition. To the right is a monumental study of Jesus’s hand pierced by a nail and the words “His pain is your gain,” underlining the artists’ belief that Jesus died for all of our sins.

In a photo of a similarly admonitory mural, Doorway to Hell, Racioppo takes advantage of the warm amber light of midmorning to burnish the grim vision of hell that is his subject. Like The Sin of the World, this mural also uses the building’s structure to frame and organize the composition: the arched entryway opening into hell is painted on a cinder-block wall (once probably a storefront) at the approximate height and scale of an actual doorway. This entrance to the netherworld is guarded by three devil-like gargoyles painted above the double doors, along with the number 666. At the top of the mural, “Doorway to Hell” is spelled out in crimson letters dripping with blood, and flames flicker out from the crack between the closed doors. A pair of sinister eyes stares out from a slot in the door marked with the words “Enter at Your Own Risk.” Flanking the doorway are the phrases “Not Only Blacks but Also Whites!” and “Just Think about It!” The artist seems to suggest that despite hell’s ferocity, all is not lost: eternal damnation is not a given, but rather the result of the deliberate choices we make every day.

The mural subject of Bad Boys Go to Heaven appealed to Racioppo because of its affirmation, spelled out in large, boldly stylized letters, that “Bad Boys Go to Heaven Too.” Says Racioppo: “The graffiti earth angels and sayings like this make me wonder—Is there a heaven? Can you play basketball there? Do ‘bad boys’ go to heaven? I don’t know.” At the left is a figure in a knit cap, his long, crossed arms terminating in enormous hands, who recalls the portrait of the DJ in Crazy Legs. (The two murals may be the work of the same artist, who here signs himself “Puppet.”) This figure holds a can of Krylon spray paint, suggesting that this may be a self-portrait. Though the style here is similar to that of the memorial murals, this piece actually carries a birthday wish. Perhaps this mural was a gift to a friend or family member. A second figure—most likely the “bad boy” whose birthday Puppet celebrates—sits enthroned in a monumental, skull-armed chair, a glint in his eye.

Although Racioppo is attuned to deliberate instances of public devotion, he is always open to the random epiphany. Other pieces are found collages of the detritus of the street, or in the marketplace. In one early piece, Shoppers, Racioppo stumbles on an image of Christ crowned with thorns amid the commerce of daily life, in a market stall surrounded by dresses and lamps. The photograph documents the transmission and appropriation of the kinds of sacred imagery that can go almost unnoticed in the city.

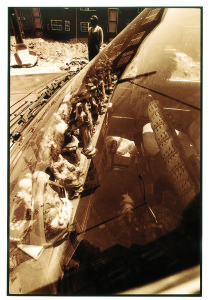

Plate 5. Larry Racioppo. Dashboard Altar, 1993. East 167th Street near Prospect Avenue, the Bronx. 20 X 16 inches. 35 millimeter black-and-white negative.

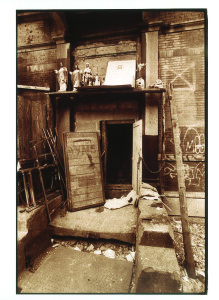

Plate 6. Larry Racioppo. Entranceway Altar, 1990. West 120s or 130s near Lenox Avenue, Manhattan. 20 X 16 inches. 35 millimeter black-and-white negative.

Although a large part of Racioppo’s work deals with the religious imagery he finds out on the street, he has always been interested in the ways in which devotion is expressed in the private sphere. As early as 1976, he began to photograph his family’s shrines in such works as Aunt Kitty’s Altar. Over time, he broadened his range to include public and private expressions of devotion outside his family circle. Racioppo has photographed shrines on church grounds, privately sponsored corporate shrines, as well as shrines in private yards and even cars. But some of the most striking occasions of private devotion are found in people’s homes, even the most humble [see Plates 5 and 6].

Because of his work for the city’s housing department, Racioppo has developed an unusually in-depth firsthand knowledge of the various forms that privately expressed devotion can take. He has been able to photograph (always with permission) the many shrines he comes upon in the buildings he visits. These include traditional Catholic devotional displays and more individualistic altars that mix sacred and profane objects. One intriguing example is Refrigerator Altar with Trolls. Set on top of a white refrigerator, the altar consists of an open Bible, offerings of bread and money, a small devotional statue of Jesus draped with a popcorn garland, and three plastic skateboard-riding trolls.

Some of Racioppo’s most haunting scenes have been captured in vacant apartments, like Apartment Door Diptych. Here, two panels show both sides of a soiled and battered apartment door on which are stuck sheets of paper covered with bold religious statements. Hand-lettered signs in multiple colors on dot-matrix computer paper are stuck to the door’s exterior. They read:

I shall give and declare the works of my God. Satan you’ve tried to destroy me and the works for God’s glory. But, I will not die you can’t stop me block me kill me or destroy me or works of my hands. In Jesus name.

To the right is a small 1991 wall calendar opened to the month of January, printed with two biblical quotations: “Who can bring a clean thing out of an unclean? No one! (Job 14:4)” and “The blood of Jesus Christ His (God’s) Son cleanses us from all sins (1 John 1:7).”

Photographing both sides of the door from within the apartment, Racioppo puts the door forward as a kind of spiritual buffer, conveying a sense of the comfort and security that a belief in God can offer. On the inside, a sign affixed at the top of the door reads: “No weapon formed against me will shall prosper. Thanks Lord. Board of honest report those incensed against me be as nothing strive with me, will perish.” Similar signs are barely visible in the shadows to the left of the doorway. Below, another sign, written hastily in red marker on a piece of brown corrugated cardboard, reads: “No more bldgs sunwers wealth is mine blood of Jesus token on 140 St. Bldgs. (Devil is a liar) For God’s glory only.” Posted beside a row of locks and a deadbolt, it may refer to its author’s eviction from the apartment, a protest against the injustice of the city’s decision. Beneath hangs a 1986 calendar sponsored by the “Christian Jew Foundation.” Opened to the month of September, it features a landscape with a quotation from Matthew 2:23, “He shall be called a Nazarene.” Apartment Door Diptych embraces these statements that call out from the door of the now empty home, offering a last testament to its former inhabitant.

Mary Statue and Halloween Decoration reflects Racioppo’s fascination with the way one Brooklyn family incorporates the Mary shrine in their courtyard into their seasonal decorative schemes. In the photograph, the shrine is decked out for Halloween, its small garden filled with cartoon images of a friendly green witch and a jolly ghost, with fake cobwebs draped all around. The entire courtyard is decorated for the season, with a near life-sized Frankenstein, a string of pumpkin-shaped lights, and bed-sheet ghosts. For Racioppo, this commingling of the sacred and the secular suggests that the shrine is a vital part of the lives of the family that assembled it.

In his 2004 Lisanti Family Chapel series, Racioppo returns to one of his earliest themes, Italian American Catholicism. After reading a feature on the chapel in the New York Times, Racioppo contacted folklorist Joseph Sciorra, who has studied the building extensively and who put him in contact with the family. Built in 1905 by Francesco Lisanti as a private devotional space, the chapel stands intact today but is little used and remains unlit. Using a large-format camera and a twenty-minute exposure combined with repeated flashes, Racioppo captures the careful detailing of the interior, composing a beautifully illuminated shot in spite of the dimness. Drawn by the chapel’s “haunting beauty and presence, and the energy it possesses,” Racioppo conveys the silence and solitude that time and, with it, a dramatically altered context have brought to the little chapel. The Lisanti Chapel stands on a Bronx street that has changed greatly over the hundred years since it was built. Like the little house in Virginia Lee Burton’s eponymous children’s story, the chapel has seen an urban environment grow up around it, isolating it within its original space. In an exterior shot, Racioppo sets the chapel solidly within its twenty-first-century streetscape, a lonely monument to the deeply rooted familial piety and religious devotion that spurred its construction more than a century ago.

Like the little chapel, Larry Racioppo has seen his neighborhoods and his city change greatly since the 1970s. Developed over decades of living and working in New York, his familiarity with and unique access to various neighborhoods in the five boroughs have resulted in a body of work of both breadth and depth.

As a citizen of New York, Larry Racioppo is interested in how religious devotion is incorporated into the lives of his city’s diverse communities. Although his photographs focus on the neighborhoods he is most familiar with—where he has and continues to live, work, and play—they underscore the vitality of certain Christian images that surface over and over again across the cityscape. Taken together, the photos collected in The Word on the Street make visible what city dwellers often miss, though it is right there in public view: the religious devotion that is part of many of our neighbors’ daily lives—in all its strange, unexpected beauty.